Background to the James Cook Heritage Trail

This section provides background information that will enhance your understanding and enjoyment of the James Cook Heritage Trail:

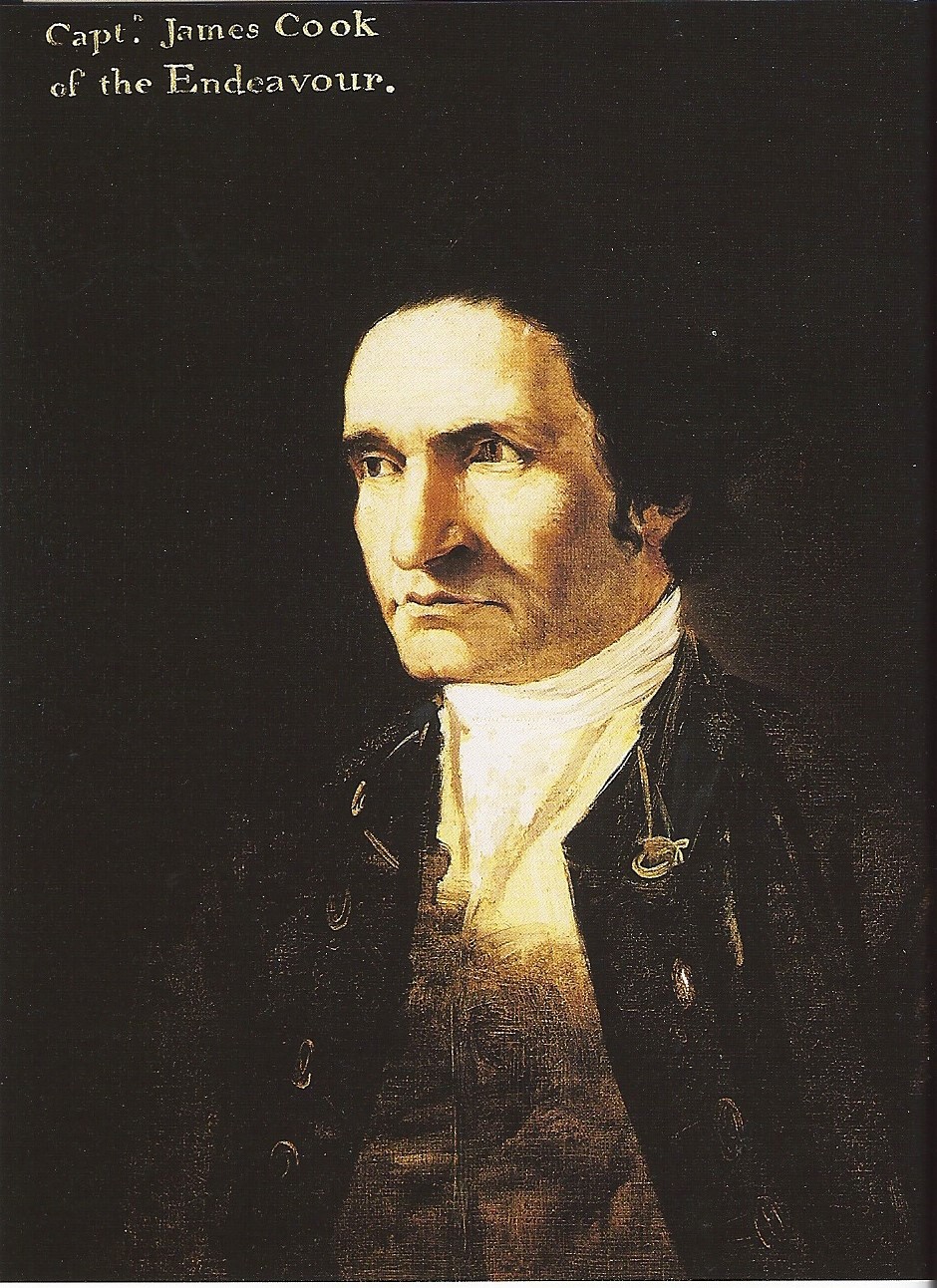

James Cook (often referred to as Çaptain Cook) was an eighteenth century British explorer and scientist. He is best known to Australians as, in 1770, the first European explorer of the east coast of this continent. His voyage in HMB Endeavour led, 18 years later, to the establishment of a British penal colony at Sydney Cove and ultimately to the establishment of several British colonies on the continent. British control of the continent was effectively relinquished on 1 January 1901 when the Commonwealth of Australia was established, however Britain’s monarch, Elizabeth II, is also Australia’s Head of State and remains as Queen of Australia. The Endeavour voyage was to be the first of three voyages Cook made to the Pacific Ocean, and is also referred to as his First Voyage.

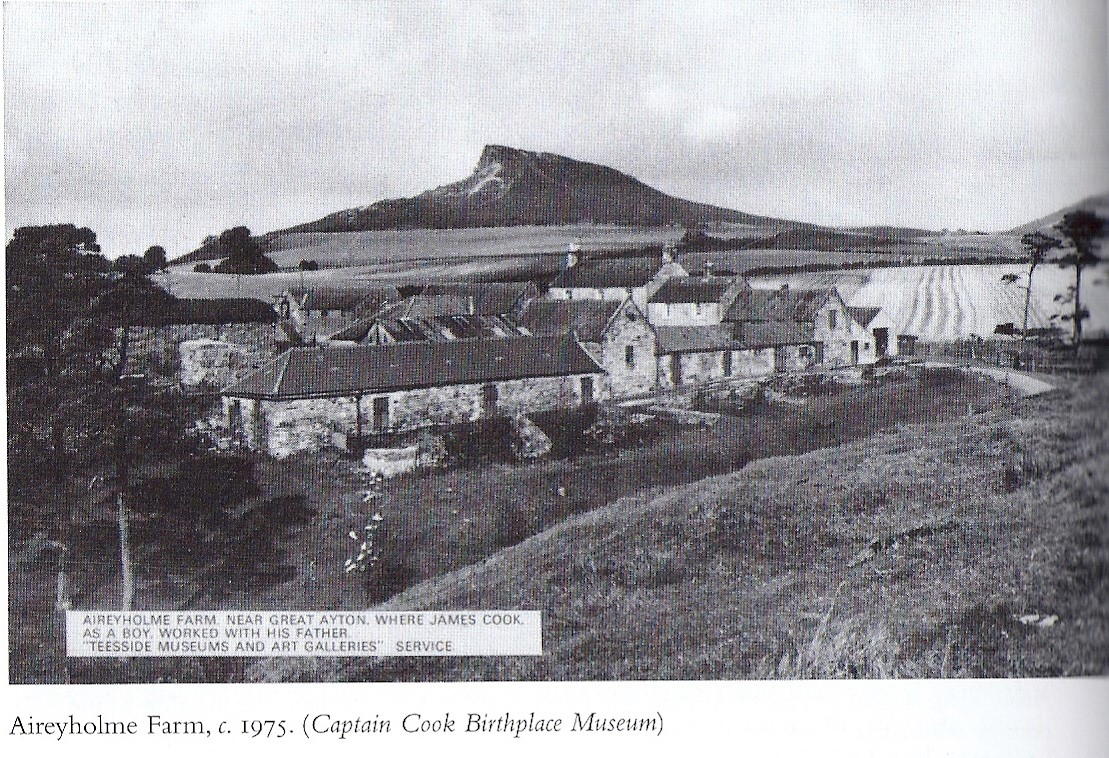

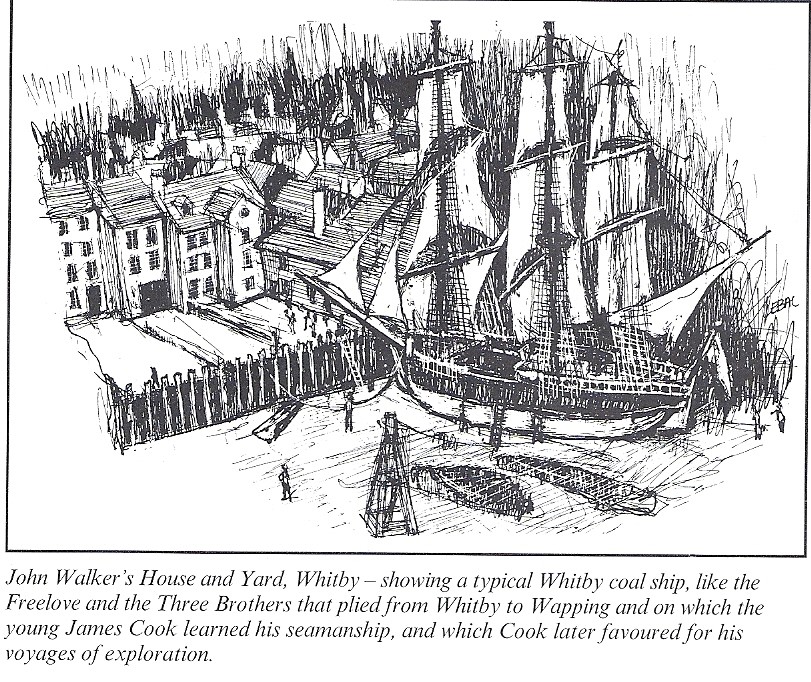

Born in 1728, James Cook rose from humble beginnings as the son of a farm labourer in northern England. He worked hard to gain a basic education and at 17 became an apprentice seaman with ship owner John Walker at Whitby. He applied himself to his work and study and by the age of 26 was offered command of one of Walker’s ships carrying coal from northern England to London.

Instead, keen for adventure, in 1755 he decided to join the Royal Navy. He quickly rose to more responsible positions because of his skills as a sailor and navigator, and his ability to inspire results from the sailors under him. He came to the notice of naval officers who encouraged his study of mathematics, navigation and astronomy, and he quickly became one of the British Navy’s most proficient navigators. His expertise, ability and hard work prompted the navy to give him command of a small sailing ship and task him with charting the complex coast of Newfoundland. He spent his summers of 1763 to 1767 surveying these coasts and his winters in London drawing up his charts.

This cottage, which James Cook never lived in but visited once, was brought to Australia in 1934 and re-erected In Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne.

His special skills brought him to the attention of the highest ranks of the Royal Navy, especially as he had established a reputation for achieving and surpassing the often ambitious sets of orders given to him by the British Admiralty. In 1768 he was chosen to command HM Bark Endeavour on a scientific voyage to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus across the sun, an important piece of science which would enable the earth’s distance from the sun to be calculated. It was the beginning of the scientific age, an Age of Enlightenment, when people in Europe became interested in studying the world around them and pushing the boundaries of new sciences such as botany, zoology, and astronomy. On board Endeavour were a number of trained scientists including Joseph Banks, a rich young man with a particular interest in botany, and his assistant Daniel Solander. Cook’s astronomy skills qualified him, besides being in charge of the ship, to be appointed as assistant astronomer to conduct the observations required for the Transit of Venus.

Cook had instructions about what he had to achieve on the voyage, both from the Admiralty and from the Royal Society, the leading scientific body of the day. Lord Morton, President of the Royal Society, and a leading Enlightenment figure, charged him with the responsibility:

To exercise the utmost patience and forebearance with respect to the Natives of the several Lands where the Ship may touch. To check the petulance of the Sailors, and restrain the wanton use of Fire Arms. To have it still in view that sheding the blood of these people is a crime of the highest nature… They are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit… They may naturally and justly attempt to repell intruders, whom they may apprehend are come to disturb them in the quiet possession of their country, whether that apprehension be well or ill founded.’ Therefore every effort should be made to avoid violence; if it became inevitable, then ‘the Natives, when brought under, should be treated with distinguished humanity, and made sensible that the Crew still considers them as Lords of the Country.

During his voyages Cook was always respectful of the traditional owners of lands which he visited, displayed a strong interest in learning about their culture, and did his utmost to maintain good relationships.

Cook was a humane man and had already demonstrated great care for the sailors aboard the ships he served on. At that time scurvy was a disease which killed many sailors on long voyages and its cause, vitamin C deficiency, was not then understood. Cook went out of his way to ensure that his crews remained healthy by ensuring that they were supplied with, and ate, fresh foods and preserved foods such as sauerkraut and preserved citrus fruits which were known to help in preventing scurvy. As a result of these and other measures, the crew of Endeavour remained healthy and morale was high.

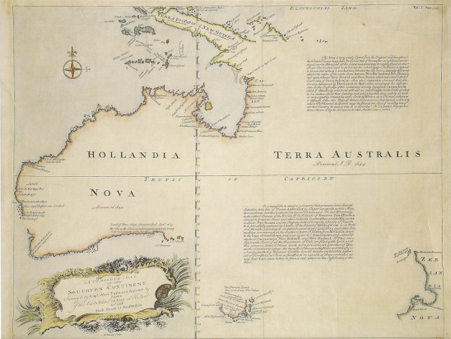

Besides making observations of the Transit of Venus, Cook had orders from the Admiralty to search for the Great South Land. At this time there was a theory that there were large undiscovered continents in the southern hemisphere to balance the extensive land masses in the northern hemisphere. Cook’s voyages were largely responsible for disproving this theory and revealing the vastness of the Pacific Ocean. From Tahiti he sailed south and then west eventually reaching today’s New Zealand. He circumnavigated, and was first to chart, New Zealand, proving it was two islands and not part of a large continent.

Having successfully completed the tasks required by his orders from the Admiralty, Cook was then at liberty to return to England by any route that he chose. While the north, west and part of the south coast of the Australian continent had been roughly charted by Dutch sailors (notably Abel Tasman) many years before, the south eastern and east coasts had not been seen by Europeans. After 20 months at sea Cook’s ship Endeavour was in a poor state of repair and the crew were eager to get home. After consulting his officers Cook decided to look for the east coast of Australia, follow it north to the Torres Strait, and head west to a Dutch outpost at Batavia (today’s Jakarta) where repairs to the ship could be made.

Chart of New Holland showing the coasts charted prior to Cook’s arrival. Note that parts of Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) and New Zealand had been visited by Dutchman Abel Tasman in the 1640s. The existence of the Torres Strait between Australia and Papua New Guinea was still uncertain at this time

Short of supplies and with a failing ship, Cook could only make a running survey of the east coast of Australia. There was no time to land and explore as thoroughly as he had done in Tahiti and New Zealand, but he did need to stop to obtain fresh water and wood for the ship’s cooking stoves. His main landings were made at Botany Bay and at today’s Cooktown, North Queensland. At both places he attempted to make contact with the local people, but with limited success.

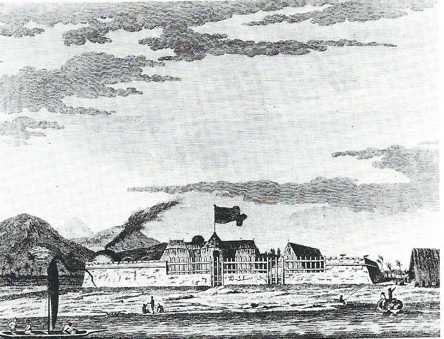

This was in stark contrast with his experience at Tahiti where an extended stay was required to set up the observatory and make observations of the Transit. The Tahitians had received earlier visits from Europeans and were more familiar with their technology and lifestyles. First and early contacts between cultures are always difficult for both parties and there is much scope for misunderstanding, suspicion of motives, and fear of attack. Cook, who himself was completely new to such a situation, faced huge difficulties. He needed to carry out his orders and make the Transit observations, and to obtain food and water for nearly 100 people on board Endeavour. This required building a good working relationship with the leaders and people on the island as well as keeping his sailors under control. Inevitably there were incidents and misunderstandings, but the good sense of the local leaders and Banks and Cook ensured that these were overcome and peace and good relations were maintained.

‘Venus Fort, Erected by the Endeavour’s People, to Secure themselves during the Observation of the Transit of Venus at Otaheite’. Engraving by S. Middiman after Sydney Parkinson, 1773.

Banks’ and Cook’s Enlightenment values not only assisted in building understanding and strong relationships with the Tahitian people, but ensured that they learned and recorded much about the Tahitian way of life and language. Their records of Tahitian life are recognised today as the beginnings of social anthropology.

Cook made two further great voyages to the Pacific. On the second voyage (1772-1775) he and his crew explored new areas in the Pacific and became the first humans to cross the Antarctic Circle. On the fateful third voyage commencing in 1776, Cook’s main task was to find the North West passage linking the north Pacific with the north Atlantic Ocean. He surveyed the north west coasts of America and crossed the Arctic Circle, but his progress was blocked by ice. Returning to the Hawaiian islands, Cook and others on both sides were killed in a fight in February 1779.

More recently James Cook has become a controversial figure in Australian history, and has been associated with the dispossession of the indigenous custodians of the continent which followed the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. This is despite the fact that Cook had died several years prior to the First Fleet’s arrival. In the lead up to the 250th anniversary of Cook’s arrival on the Australian coast, and with growing understanding and appreciation of the impact of the arrival of outsiders on the one hand and, on the other, a better appreciation of Cook’s role in these events, there are encouraging signs that Cook is emerging as an important and more benign figure in indigenous history. In recent years at both Botany Bay and at Cooktown, the two sites where Cook spent most time ashore, mutually respectful relationships have developed as people work together every year to commemorate the anniversary of Cook’s arrival.

In this way Cook has begun to emerge as a force for reconciliation, a role that this humane man would have greatly appreciated. As he left these coasts he recorded his impressions of its people in a respectful manner:

From what I have said of the Natives of New-Holland they may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholy unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary Conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturbed by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them will all things necessary for life, they covet not Magnificent Houses, Household-stuff etc, they live in a warm and fine Climate and enjoy a very wholesome Air, so that they have very little need of Clothing and this they seem to be fully sencible of, for many to whome we gave Cloth etc to, left it carlessly upon the Sea beach and in the woods as a thing they had no manner of use for. In short they seem’d to set no Value upon any thing we gave them, nor would they ever part with any thing of their own for any one article we could offer them; this in my opinion argues that they think themselves provided with all the necessarys of Life and that they have no superfluities.

There are many biographies of James Cook. Richard Hough’s ‘Captain James Cook: a biography’ is still regarded as one of the best and is readily available new or secondhand. Alan Villiers (himself a man who had sailed on sailing ships), provides a unique seaman’s perspective on Cook, giving an insight into shipboard life in Captain Cook: The Seaman’s Seaman. J.C Beaglehole’s The Life of Captain James Cook is still regarded as the standard reference.

The Captain Cook Society is an international organisation for Cook enthusiasts and publishes a fascinating quarterly journal Cook’s Log. See their excellent website which has lots of useful information: https://www.captaincooksociety.com/. In Australia there are two chapters, one in Sydney and another in Melbourne, which hold regular meetings and talks.

For recent published research relating to Cook Landmarks in Victoria and New South Wales that are, or are believed to be, in the wrong place on today’s maps and charts, go to:Restoring Cook’s Legacy 2020 Publications

Endeavour’s Journal and Log

Want more detail about day to day life during Endeavour’s voyage?

The day to day records of the Endeavour voyage, recording ‘remarkable occurrences’ (or things worth noting) are contained in the ship’s Journal. The print version edited by J.C. Beaglehole, The Journals of Captain James Cook: The Voyage of the Endeavour, 1768-1771, is regarded as the standard reference and the quotations from the Journal on this website are drawn from this source. There are plenty of online sources for the Endeavour Journal e.g: http://southseas.nla.gov.au/index_voyaging.html Read the original in Cook’s own handwriting from the copy in the National Library of Australia at: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-228958440/view

The ship’s Log is an hour by hour record of Endeavour’s voyage which contains much interesting information such as distance travelled, ship’s compass course, wind directions, as well as brief information about the day to day activities on board that supplements entries in the Journal. You can read an original at: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-517532598/view?partId=nla.obj-558521253

Both the ship’s Journal and Log are recorded in ship’s time with each day commencing not at midnight but at noon, civil time. So, Cook arrives off the coast of Victoria, according to Endeavour’s Journal at 6 a.m. on 19 April 1770, ship’s time, that ship’s day having commenced 18 hours earlier at noon. But 6 hours previously at midnight civil time (which runs midnight to midnight) the civil time date had changed from 19 to 20 April. This means that according to civil time Cook arrives off the coast on 20 April, not the 19th as in the Journal. To avoid confusion this website refers the times and dates given in the Journal and Log, with the ship’s day 12 hours behind the civil day.

Leagues and Longitudes - Understanding Cook’s Journal

Reading the Journal extracts:

Despite his lack of formal education, Cook’s descriptions of the Landmarks he named are usually brief, but precise and accurate. 250 years later it is easy for the modern reader to understand most of Cook’s Journal entries, though sometimes the spelling can be a little different!

Distances:

Before you start to read it is useful to understand that Cook worked with measures of distance that are quite different to those we use today – metres and kilometres. The table below gives conversions. Cook deals in leagues and nautical miles. It is worth trying to remember that 1 league = 3 nautical miles or 5.56km, and that a nautical mile is just under 2km.

Latitude and Longitude:

Cook gives Endeavour’s position, and that of Landmarks, in Latitudes (so many degrees south of the Equator) and Longitudes (so many degrees west of Greenwich (London, UK)). The convention today is to give longitudes up to 180 degrees east and west of Greenwich, whereas Cook gives them all as west of Greenwich, so you will see ‘Long 207.30 W’. If you deduct this from 360 degrees you will get 152.30 E’, the modern way of expressing it. You will see that in the Journal Cook often gives his position at noon. This is because the sun is at its highest point at noon and it was easy to work out Latitude from the angle at which the sun appeared at that time. Longitudes were far more difficult. Cook carried lunar tables, a new technology which involved complex calculations following observations of the moon and certain stars. Because of these and other difficulties Cook’s latitudes and longitudes do not always coincide with modern positions.

On later voyages Cook carried the time at Greenwich with him in the form of a chronometer which made things so much simpler. If the chronometer was kept wound up and was of good quality he would at all times know the time at Greenwich. From his daily sun shot he would know when it was noon where he was, and so it was easy to calculate how many degrees he was from Greenwich. For example, at noon at 180 degrees from Greenwich, a chronometer would show it was midnight at Greenwich. If at noon locally the chronometer showed 1a.m at Greenwich Cook would know that he was 11 hours ahead of Greenwich, with every hour representing 15 degrees of longitude, and that he was at 165 degrees east.

Cook expresses latitudes and longitudes in degrees and minutes, a minute being one sixtieth of a degree. Modern coordinates are often expressed in decimal form, in degrees and hundredths of degrees – so Cook’s 207.30 W would become 207.50 W or 150.50 E. Modern coordinates in decimal form are given for each of the Cook Landmarks described on this website to enable you to punch this info into your smartphone and find your way to them.

Points of the compass:

In the Journal and Log Cook gives the ship’s course, wind directions, and bearings to land features in abbreviated form, e.g. W, NW, NNW, NbW. There are 32 points to the compass. Each Point = 11 ¼ degrees. The 32 points of the compass are N, Nb(by)E, NNE, NEbN, NE, ENE, EbN, E, EbS, ESE, SEbE, SE, SEbS, SSE, SbE and so on back to N)

Conversions:

1 foot = 30.48 Centimetres

1 fathom = 1.83m or 6 feet

1 nautical mile = 1.853 kilometres (6080 feet or one minute of latitude in the latitude of Great Britain). Cook’s distances are given in nautical or sea miles.

1 knot = 1 nautical or sea mile per hour

1 league = 3 nautical miles or 5.56 kilometres

degree = 1/360 of the circumference of a circle

minute = 1/60 of a degree

second = 1/60 of a degree

Note that Cook usually shows only degrees and minutes, not seconds. Modern latitudes and longitudes often appear as degrees and 1/100 of a degree, using the decimal system.

Reading the Journal extracts:

Despite his lack of formal education, Cook’s descriptions of the Landmarks he named are usually brief, but precise and accurate. 250 years later it is easy for the modern reader to understand most of Cook’s Journal entries, though sometimes the spelling can be a little different!

Distances:

Before you start to read it is useful to understand that Cook worked with measures of distance that are quite different to those we use today – metres and kilometres. The table below gives conversions. Cook deals in leagues and nautical miles. It is worth trying to remember that 1 league = 3 nautical miles or 5.56km, and that a nautical mile is just under 2km.

Latitude and Longitude:

Cook gives Endeavour’s position, and that of Landmarks, in Latitudes (so many degrees south of the Equator) and Longitudes (so many degrees west of Greenwich (London, UK)). The convention today is to give longitudes up to 180 degrees east and west of Greenwich, whereas Cook gives them all as west of Greenwich, so you will see ‘Long 207.30 W’. If you deduct this from 360 degrees you will get 152.30 E’, the modern way of expressing it. You will see that in the Journal Cook often gives his position at noon. This is because the sun is at its highest point at noon and it was easy to work out Latitude from the angle at which the sun appeared at that time. Longitudes were far more difficult. Cook carried lunar tables, a new technology which involved complex calculations following observations of the moon and certain stars. Because of these and other difficulties Cook’s latitudes and longitudes do not always coincide with modern positions.

On later voyages Cook carried the time at Greenwich with him in the form of a chronometer which made things so much simpler. If the chronometer was kept wound up and was of good quality he would at all times know the time at Greenwich. From his daily sun shot he would know when it was noon where he was, and so it was easy to calculate how many degrees he was from Greenwich. For example, at noon at 180 degrees from Greenwich, a chronometer would show it was midnight at Greenwich. If at noon locally the chronometer showed 1a.m at Greenwich Cook would know that he was 11 hours ahead of Greenwich, with every hour representing 15 degrees of longitude, and that he was at 165 degrees east.

Cook expresses latitudes and longitudes in degrees and minutes, a minute being one sixtieth of a degree. Modern coordinates are often expressed in decimal form, in degrees and hundredths of degrees – so Cook’s 207.30 W would become 207.50 W or 150.50 E. Modern coordinates in decimal form are given for each of the Cook Landmarks described on this website to enable you to punch this info into your smartphone and find your way to them.

Points of the compass:

In the Journal and Log Cook gives the ship’s course, wind directions, and bearings to land features in abbreviated form, e.g. W, NW, NNW, NbW. There are 32 points to the compass. Each Point = 11 ¼ degrees. The 32 points of the compass are N, Nb(by)E, NNE, NEbN, NE, ENE, EbN, E, EbS, ESE, SEbE, SE, SEbS, SSE, SbE and so on back to N)

When Endeavour reached Australia’s east coast in mid April 1770 it was uncharted and unknown to the outside world. James Cook and his officers, after twenty months at sea, had decided to explore this coast rather than using the more direct route south of the Australian continent to the Cape of Good Hope. Supplies were running low, and Endeavour’s men were ‘sighing for roast beef’ and longing to be back home. The ship was in a poor state of repair and unfit for the rigours of the ‘roaring forties’, the stormy seas of the southern ocean route that would have brought it to the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. The nearest port to make repairs was at Batavia (Jakarta) in today’s Indonesia, then a Dutch colony. This involved sailing up what Cook hoped would be the eastern coast of New Holland, the Dutch name for Australia, sailing through the Torres Strait (which he was not entirely sure existed), then westward to Batavia.

Given these circumstances Cook had no time for a detailed survey but decided to make a running survey of this coast. This involved taking a compass bearing on prominent land features ahead of him, as he passed them, and then behind him, as he sailed up the coast. This information assisted him to fix his position and draw a chart of the coast. Sailing well offshore, to avoid shoals (shallow waters near the coast) and being blown onto a lee shore, meant that most of the features Cook named are elevated and distinctive, standing out from the wooded coast and hills of the hinterland.

James Cook’s did not just sprinkle place names on his chart. His practical purpose in naming land features was to assist later navigators on the coast to determine their position. In Cook’s day many captains lacked Cook’s advanced navigating skills. Many rarely ventured out of sight of land for very long, and followed coasts, relying on drawings if the coast (coastal views) and prominent features to ascertain their position. As such Cook’s named features formed an important maritime safety aid. For these reasons the land features he named are prominent and usually easily recognised from well out to sea, being distinctive mountains or cliffs, notable islands or trends of the coast. These features are truly Cook Landmarks.

Not all of these features form part of the James Cook Heritage Trail.

Features marked + are in the wrong place on today’s maps: ++ indicates features in the right place but believed by some to be elsewhere; +++ indicates a feature named by Cook that is absent from modern maps and * landmarks described but not named.

- + Point Hicks

- + Ram Head

- * Gabo Island

- ++ Cape Howe

- Mount Dromedary

- * Little Mount Dromedary

- ++ Cape Dromedary

- Bateman Bay

- * Tollgate Islands

- Point Upright

- Pigeon House Mountain

- * Brush Island

- * Racecourse Beach

- * Mount Budawang

- * Currockbilly Mountain

- + Cape St George

- * Jervis Bay

- + Long Nose

- ++ Red Point

- * Mount Keira or Mount Kembla

- * Garie North Head

- * Collins Rock

- Botany Bay

- Point Solander

- Point Sutherland

- Cape Banks

- * Bare Island

- Port Jackson

- + Broken Bay

- Cape Three Points

- * Nobby Head

- * Mount Sugarloaf

- Point Stephens

- Port Stephens

- * Cabbage Tree, Boondelabah and Little Islands

- * Tomaree and Yacaaba Heads, Stephens Peak

- +++ Black Head

- Cape Hawke

- Three Brothers

- * Tacking Point (Log)

- Smoaky Cape

- * Big Smoky

- * Little Smoky

- Solitary Islands

- Cape Byron

- * Cook Island

- + Point Danger

- Mount Warning

Collins Rock (Between Bellambi Point and Bulli) – attempted landing 28 April 1770

Botany Bay – 29 April to 6 May 1770

Click here to see the Restoring Cook Legacy section.

Restoring Cook’s Legacy 2020 is a project of Australia on the Map, the history and heritage Division of the Australasian Hydrographic Society. The Project aims to identify the correct locations of the land features that Cook named on the coasts of Victoria and New South Wales, and restore Cook’s legacy by publishing the research results (see below), sharing them through publicity, talks and events, and achieving renaming and/or heritage listing of Cook Landmarks.

To date we have identified six named land features or landmarks that are in the wrong place on today’s maps and charts (Point Hicks, Ram Head, Cape St George, Long Nose, Broken Bay and Point Danger), one that does not appear at all (Black Head), and three more that are in the correct place but are believed by some to be elsewhere (Cape Howe, Cape Dromedary and Red Point). The James Cook Heritage Trail website is an important means of bringing our research to a wider audience and promoting Cook’s legacy on these coasts.

The Restoring Cook’s Legacy 2020 Project’s Supporting Partners are:

- Australasian Hydrographic Society

- Captain Cook Society Australia

- Australian National Placenames Survey

- Placenames Australia (journal)

- South East History Group, Eden, NSW

For more information about Project activities please email us through here!

Restoring Cook’s Legacy 2020 Publications:

Below are the publications by Australia on the Map (AOTM) members correcting the errors and misunderstandings regarding Cook's named land features on the coasts of Victoria and NSW in 1770.

Most of these articles are available on line. Recent issues of ‘Map Matters’ appear at www.australiaonthemap.org.au under Newsletters and many are online at the National Library of Australia website at http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-287234231. ‘Cook’s Log’ is the Journal of the Captain Cook Society and several of the articles below appear in full on www.captaincooksociety.com

‘Placenames Australia’ articles are at www.anps.org.au/newsletter.php?pageid=3

Point Danger:

Rupert Gerritsen, 'A Dangerous Point: Fingal Head and Point Danger', Placenames Australia, June 2013, and 'A Dangerous Question', Map Matters, Issue 16, December 2011.

Black Head:

Robert King, 'Putting Broughton Islands on the Map', Map Matters, Issue 14, June 2011, and Journal of Australian Naval History, vol. 9, No. 1, March 2012.

Broken Bay:

Trevor Lipscombe, ‘Broken Bay – the mystery of Cook’s two latitudes’, Cook’s Log, Vol. 41, No. 4, October – December 2018, ‘Lt James Cook’s Broken Bay’, Map Matters, Issue 34, Winter 2018. http://www.australiaonthemap.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Map_Matters_34.pdf

Long Nose and Cape St George:

Trevor Lipscombe, 'Jervis Bay - what Lt James Cook really named', Placenames Australia, June 2017 (online at Placenames Australia website), and 'James Cook at Jervis Bay - How the chart makers got it wrong', Map Matters, Issue 30, February 2017. http://www.australiaonthemap.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Map-Matters-30.pdf ‘Where are Cook’s Cape St George and Long Nose?’, Cook’s Log, Vol 41 No 2, April-June 2018. 'Lt James Cook's misplaced capes at Jervis Bay', submitted for consideration for publication to Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. This is an extended article.

Cape Dromedary:

Trevor Lipscombe, ‘Where is Cook’s Cape Dromedary?’ Cook's Log, Journal of the Captain Cook Society, Vol 41, No 1, January 2018, and 'Cook's Cape Dromedary - is it Montague Island?’, Map Matters, Issue 32, September 2017. http://www.australiaonthemap.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Map_Matters_32.pdf

Cape Howe:

Trevor Lipscombe, 'Is Cook's Cape Howe really Telegraph Point?', Map Matters, Issue 32, September 2017. http://www.australiaonthemap.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Map_Matters_32.pdf A similar article, 'Contested Borders - is Cook's Cape Howe really Telegraph Point', Placenames Australia, March 2018. See also an extended article 'Lt James Cook on the coast of Victoria 1770;’ Victorian Historical Journal, Vol 89, No 2, June 2018.

Ram Head:

Trevor Lipscombe, 'Ram Head - a remarkably overlooked point', Cook's Log, Vol 34, No 4, 2011, p18 (on Captain Cook Society website, search for Ram Head), and 'Rame Head - misnamed and misplaced', Placenames Australia, September 2013 (online at Placenames Australia website). This has some additional information on the Ram or Rame controversy. See also 'Lt James Cook on the coast of Victoria 1770', Victorian Historical Journal, June 2018. This article contains updated information on the Ram or Rame controversy, proving that Ram was the spelling used for the UK feature at the time of Cook.

Point Hicks:

Trevor Lipscombe, 'Point Hicks - the Clouded Facts', Victorian Historical Journal, Vol 85 No 2, December 2014, pp 232-253, and 'Cook's Point Hicks: The error that just won't go away', Cook's Log, Vol 38 No 2, 2015, p18, available on Captain Cook Society website - search Point Hicks. This is a shorter version of the VHJ article, with some minor additions. See also 'Lt James Cook on the coast of Victoria 1770', Victorian Historical Journal, June 2018. ‘Cook’s Point Hicks: Reports from the 1870s’, Cook’s Log, Vol 41, No 3 (2018).

Why visit?

History should live and breathe, not be confined between the covers of books. A primary purpose of this website is to encourage people to visit these Cook Landmarks and see the features that Cook himself saw and named 250 years ago. There is a special excitement and a sense of connection that comes from visiting a remote spot and finding it is just as it was when Cook and his men were the first Europeans to set eyes on it so long ago. There are still many landmarks which are much as they were when Cook saw them. Cook and Banks etc were here – and this is what they saw! At these places it is easy to imagine the billowing sails of Endeavour approaching and nearly a hundred men at their daily life on board. Cook and Orton working on the Journal, Parkinson, Solander and Banks examining plant specimens collected in New Zealand or at Botany Bay, sailors aloft tending the sails or below steering the ship and scrubbing the decks. A busy space capsule thousands of miles from the nearest European outpost. As Ray Parkin reminds us in his remarkable book ‘H. M. Bark Endeavour’:

What was happening during April 1770 was that a small group of men and a small ship were sailing over a blank space on the world map and observing the sea and shore in such a way , and with such understanding, as to be able to place it on a map with unprecedented accuracy, very much as it would still be placed more than two hundred years later, and having as their only reference points the Equator and Greenwich, 13000 miles away.

In Victoria and New South Wales it is only at Botany Bay that it is possible to stand where Cook stood, and this site is one of the least remote. Walk onto the rocks and find the plaque that marks the point where young Isaac Smith, Cook’s wife Elizabeth’s cousin, was the first to step ashore on 29 April 1770.

The words of explorer and navigator John Lort Stokes still ring true of any Cook landmark. Climbing the hill in 1839 on remote Lizard Island off Cooktown, North Queensland, from where Cook in 1770 had looked with trepidation for a passage out of the Great Barrier Reef, he wrote:

There is an inexpressible charm in thus treading in the track of the almighty dead, and my feelings on attaining the summit of the peak… will easily be understood. If I felt emotions of delight… how much stronger must have been the feelings of Captain Cook, when from the same spot years before, he saw by a gap in the line of broken water, there was a chance of his once more gaining the open sea.

Visit these places and put yourself in the shoes of those on Endeavour 250 years ago!